Scenes from graduation events, 1966.

Scenes from graduation events, 1966.

Scenes from May Day 1966.

Moving into Oakwood Hall during the autumn of 1965 and scenes from the student Union early in the 1965-1966 academic year.

The Victory March from Wabash to Manchester occurred in late February, 1966 after winning the Hoosier Collegiate Conference Championship. One alumnus speculates that it might have been a “bet” by Coach Wolfe to make that walk if the team won. Further in the photo montage is a sign wishing for a place in the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics National Tournament in Kansas City. However, we lost to Indiana Central (now U. Indy) in the District 21 playoffs, a team we had defeated for the conference championship. Indiana Central went to Kansas City.

Homecoming 1967, and laboratory scenes.

Paul Flory ‘31 won the Nobel Prize in Polymer Chemistry in 1974 for his work with macro-molecules in polymers. Flory spoke at the Chemistry Symposium in 1975.

While at Manchester, Flory roomed with Roy Plunkett ‘32, who discovered Teflon for the Dupont Company.

Andrew Cordier, MC Class of 1922, played a major role in the founding of the United Nations. Cordier helped draft the United Nations Charter at the Dumbarton Oaks Conference and served as the executive assistant to the U.N. Secretary-General. Before serving at the U.N., Cordier was chair of the history and political science department at Manchester, served on the Manchester Board of Trustees, and at one time, served as president of Columbia University.

Cordier was influential in defining Manchester’s global emphasis, and wrote to Vernon Schwalm, who would later become president of Manchester, in 1929 about the role of the Brethren. “A war-worn world needs our philosophy and examples of peace, a luxury-mad world, with yawning chasms between rich and poor, needs our examples of the simple life.”

After years of work from President Helman, rescheduling because of bad weather, and increasing security because of threats from the community, Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his final campus address at Manchester on February 1, 1968, almost two months before his assassination. The college brought Republican Presidential candidate Barry Goldwater to campus the week after to appease community members.

The civil rights leader presented “The Future of Integration” in a full gymnasium.

President Helman, members of the faculty, members of the student body of this great institution of learning, ladies and gentlemen, I need not pause to say how very delighted I am to be on the campus of Manchester College and to have the privilege of sharing with you in this convocation setting. I should say that I’m happy for several reasons. One reason is that Reverend Young and I flew out of Chicago this morning, and as soon as we got on the flight, we were reminded of the fact that the weather was pretty bad on the way in, and after we got up, we experienced the fact in actual terms because it was quite turbulent and we landed first in South Bend and then in Fort Wayne. And whenever I find myself on a very turbulent, trepid flight I’m always very happy to get on the ground. Now I don’t want you to get the impression that I don’t have faith in God; but it’s just that I’ve had more experience with Him on the ground …

I want to use as a subject from which this speech this morning is taken “The Future of Integration.” There is a desperate, poignant question on the lips of millions of people all over our nation and all over the world. They constantly ask whether we have made any real progress in the area of race relations. There are those who feel we have made very little progress and there are those who are quite optimistic in their analysis and their outlook and they feel we have made tremendous strides. When I think of the problem, I try to emerge with what I consider the realistic form of view. That realistic point of view leads me to say on the one hand that we have made some meaningful strides in the struggle for racial justice, but leads me on the other hand to say that we still have a long, long way to go. It is this realistic position that I would like to use as the basis for our thinking together today. We have come a long, long way; but we still have a long, long way to go before racial justice is reality in our nation. Let us begin with the fact we’ve come a long, long way…

King, Martin Luther, Jr. “The Future of Integration.” Manchester College Gymnasium. North Manchester, IN. 1 Feb. 1968. Address.

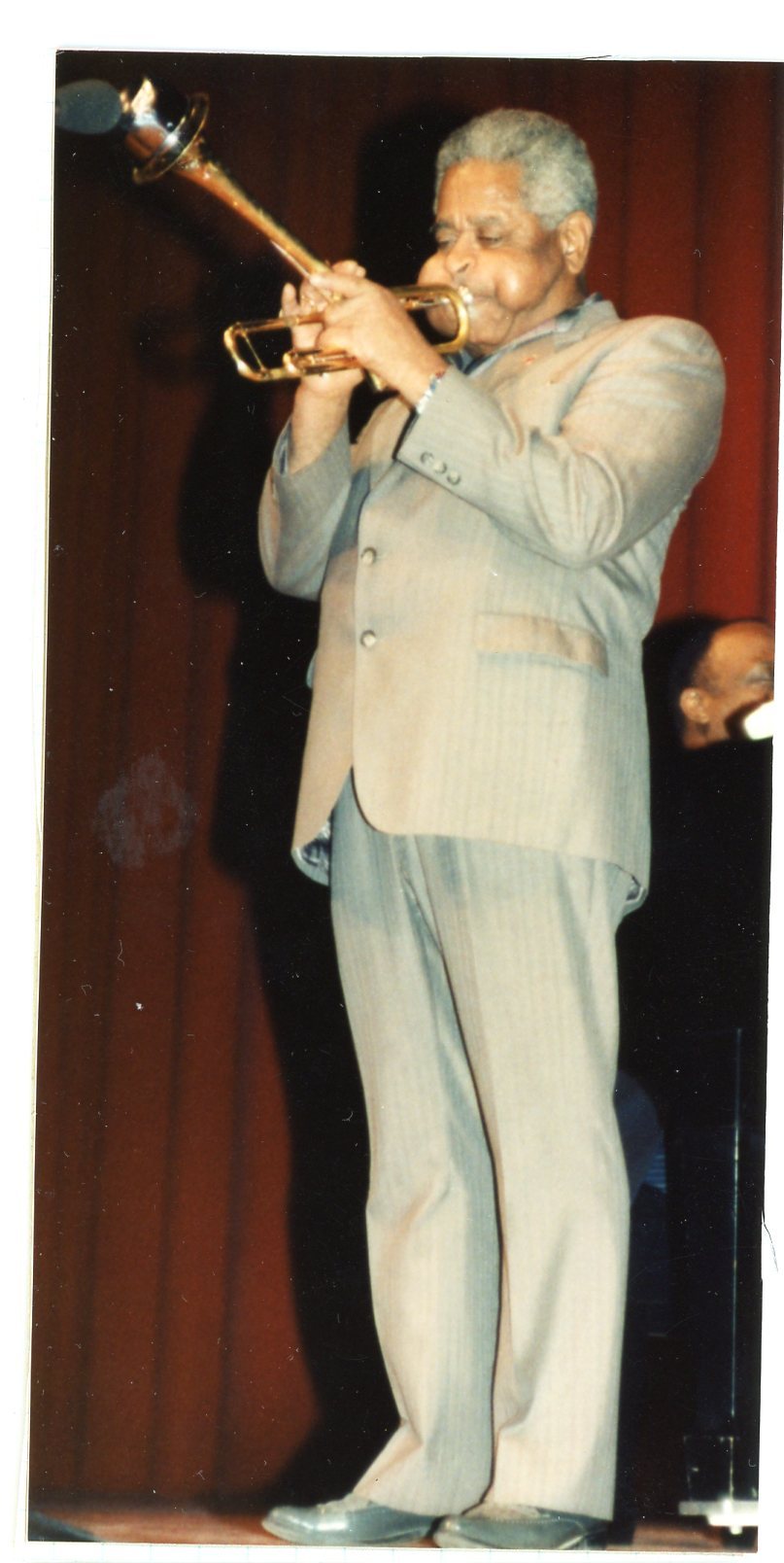

Dizzy Gillespie, famed American jazz trumpeter, bandleader and composer, travelled to Manchester to perform in 1987. Gillespie performed for the 25th Season Spectacular Artist-Lecture Series.

Other artists and groups involved in the series were the Mitchell-Ruff Duo, “The Dybbuk” featuring The National Theatre of the Deaf, Dr. Ernest Boyer, Public Affairs Lecturer, Eastman Brass Quintet, Baroque Orchestra of Indiana University, Wilma Jensen, and the Harbinger Dance Company.

In February 1982, Dr. Maya Angelou, famed American writer and poet, made her way to Manchester to present a speech about issues with race, leadership, and education.

During the presentation, Angelou, a notable singer and dancer, sang an early version of one of her poems, “Take Time Out.”

When you see them

on a freeway hitching rides

wearing beads

with packs by their sides

you ought to ask

what’s all the

warring and the jarring

and the

killing and

the thrilling

all about.

Take Time Out.

When you see him

with a band around his head

and an army surplus bunk

that makes his bed

you’d better ask

what’s all the

beating and

the cheating and

the bleeding and

the needing

all about.

Take Time Out.

When you see her walking

barefoot in the rain

and you know she’s tripping

on a one-way train

you need to ask

what’s all the

lying and the

dying and

the running and

the gunning

all about.

Take Time Out.

Use a minute

feel some sorrow

for the folks

who thinks tomorrow

is a place that they

can call up

on the phone.

take a month

and show some kindness

for the folks

who thought that blindness

was an illness that

affected eyes alone.

If you know that youth

is dying on the run

and my daughter trades

dope stories with your son

we’d better see

what all our

fearing and our

jeering and our

crying and

our lying

brought about.

Take Time Out.

Angelou, Maya. The Complete Poetry. New York: Penguin Random House, 2015. Print.

Rev. Jesse Jackson visited the Manchester campus in the spring of 1969 for “Forum 69,” a three-day event. Jackson presented “An Experience in Soul,” a speech about civil rights, justice, and diversity.

Jackson, a civil rights leader, was the founder and president of the Rainbow PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) Coalition and the Director of Operation Breadbasket. Jackson ran as the first viable African American Democratic presidential candidate in 1984 and 1988.

Actor Paul Newman, know for his roles in movies such as “Somebody There Likes Me,” “Road to Perdition,” “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid," and the Pixar animated film "Cars,” visited the Manchester campus in 1968 as part of his campaign for Senator Eugene McCarthy, who was seeking the Democratic presidential nomination. It was estimated the 350 Manchester students, mostly female, greeted Newman in front of the College Union.

In a 20 minute speech standing on the back of his car, Newman stated his reasons for voting for McCarthy and urged all of the students to get involved in the political race. According to an Oak Leaves article, Newman asked, “Who all’s going to get out and vote?” After seeing only a few hands, he stated, “The one thing I don’t dig is apathy."

Dr. Andrew Young visited Manchester four times over the course of his career. Young worked with Dr.

Martin Luther King, Jr. during the civil rights movement, was appointed

as the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations under President Jimmy

Carter, and served both in Congress and as mayor of Atlanta. When he

received his honorary degree and addressed the class of 2000, it was his

fourth visit to Manchester’s campus. In 1968, he accompanied Martin

Luther King, Jr., who spoke to students about the future of integration.

Young delivered his own convocation address in 1971, and in 1978, he

was the keynote speaker at the Cordier Auditorium dedication. His first

visit to campus, in 1953, was to celebrate May Day with his fiance, Jean

Childs, who was crowned May Queen. He credits Jean, his wife of 40

years until her death in 1994, with giving him an understanding of the mission of the nonviolent transformation of society.

Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the Manchester campus in 1957 to give her speech, “Is America Facing World Leadership?” on economic aid, peace, and the United Nations. A 1957 Oak Leaves article states that Professor Paul Keller ‘35 negotiated the visit for $1,000, and Roosevelt touched on topics such as the “Eisenhower Doctrine” (which she was unimpressed by) and the chances for peace through UN leadership. Roosevelt said, “Nobody wants war and when nobody wants war, it is a good thing.” Following the speech, Roosevelt returned to the home of new President A. Blair Helman, where she had to stay because of construction at the hotel in town.

Mrs. Pat Helman wrote about the event: The first notable guest to arrive was Eleanor Roosevelt who came to us in the fall of our first year in Manchester. She arrived in a bedraggled state, sporting knee socks and tennis shoes before Nike's were born. I showed her to the guest bedroom up the long flight of stairs, and apologized because she would be sharing the bathroom with our two daughters. The door on the bathroom had to be shut carefully or one got locked inside, but I was so tense about doing everything right that I failed to give her that bit of information. Pretty soon I heard a frantic, high voice saying over and over again, “Heelp me, somebody please heelp me.” I rushed up the stairs and rescued her and as she walked back to her room she tripped on the carpet and fell flat-out in the middle of the entryway … But I picked her up as gracefully as possible, and she said she was alright and that I didn’t need to worry about her, and I didn’t because I was worrying more about dinner for ten around the table with Eleanor as the shining star. After a successful speech in the old auditorium, with the radiators banging away, we all returned to the house that was now crowded with the News Media. At one point the dean’s wife wanted to know if she could do anything for Mrs. Roosevelt, and I was sure the lady was thirsty. So I put a glass of ice water on a silver tray that Mrs. Schwalm had loaned me, and the dean’s wife went to Mrs. Roosevelt and in lowering the tray, the glass of ice water fell into our famous guest’s lap. I’m certain she returned with plenty of her own stories to tell about this little college in Indiana and the new young president and his wife who was trying hard to be the perfect hostess. That was our first guest of note. But there were many through the years, and perhaps I should write a book.

Andrew may be Manchester’s most famous Cordier, but the diplomat’s daughter, Louise, now retired in Florida, has had a fascinating life of her own as a model, actress, banker and real estate broker.

Louise lived her first 12 years in North Manchester and describes it as a safe place where she was free to wander and talk with anyone she wished. “Manchester gave me a security that led me happily in all my travels,” she reflects. Her family roots run deep. In 1836, Louise’s great-grandmother, Phoebe Ann (Harter) Butterbaugh, was the first white child born in North Manchester. In 1924, Phoebe’s granddaughter, Dorothy Butterbaugh, married Andrew Cordier and the couple accepted teaching positions at Manchester College, their alma mater.

Louise never attended the College as a student, but if campus theatrical productions “needed a little shrimp,” she says, “they would borrow me.” She took the performances seriously. Once, still a small child, Louise made her own dental appointment so she could display clean teeth on stage.

In 1944, Louise’s father took a job at the State Department in Washington, D.C., and the family, which included Louise and her older brother, Lowell, left North Manchester. The Cordiers moved to Long Island, N.Y., a few years later when Andrew became executive assistant to the secretary general of the United Nations.

Louise longed to attend acting school in New York City, but encountered reluctant parents. “Dad used to make bargains with me,” says Louise. “He said he would let me go to acting school in New York on Saturdays, if I would help out in Sunday school class.” Another time, “Dad said I could go if I didn’t join the sorority.” He “didn’t want me to be tied down to a little clique of people.”

Finally, Andrew said that Louise needed to find an occupation through which she could make a living. Following a friend’s lead, Louise became a model in New York City. Technically, her father could not complain because Louise was making more money modeling than Andrew was making at the UN.

Louise’s acting career was an overnight success. Soon she was on Broadway alongside Tom Ewell in The Seven Year Itch, starring in the role Marilyn Monroe played in the movie version.

Besides acting, Louise loved fast cars. She fell in love with Peter Collins, an English Grand Prix driver, married him after a seven-day courtship, and moved to Italy. A year and a half later in 1958, Collins crashed his Ferrari in the German Grand Prix and died on the way to the hospital. Heartbroken but resilient, Louise returned to acting, touring with Peter Ustinov in Romanoff and Juliet. She launched a television career in England and appeared on the panel of the British version of What’s My Line?

Cast as “Girl of the Week” on the Today show, a spot for models, she ended up staying for six months. When Barbara Walters was still a writer for the program, Louise co-hosted Today in 1962 with Frank Blair and John Chancellor.

- Louise Cordier in The Seven Year Itch at Fulton Theatre

- Andrew and Louise Cordier on Manchester campus

- Andrew, Lowell and Louise Cordier

- Lowell and Louise Cordier

- Louise with Tom Ewell and Marilyn Monroe

- Louise and Peter Collins

- L to R: Ralph Bunche, Dorothy Cordier, Louise Cordier, Andrew Cordier, Dag Hammarskjöld

Page 1 of 17